by Ellen Michaud

Photography by Peter Chin

What is it that gives women their strength?

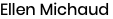

When Immaculée Ilibagiza was hunted by Hutu tribesmen in Rwanda, she hid in a four-foot-by-three-foot bathroom at her pastor's home with seven other women for three months. Outside, hundreds of blood-thirsty men with machetes screamed her name and slaughtered her family. Today, she has forgiven each and every one of them—and is working to help others in Rwanda heal from the long-term effects of genocide.

Listening to Immaculée’s story—and the stories of all of the incredible women on the following pages—is a deeply humbling experience. In the worst of circumstances, when men, women, and children were hurting or in danger, each of these women put aside her own life, her own needs, and held out a helping hand. They did what had to be done to feed families, mobilize the physically challenged, save children, comfort the homeless, and heal the soul.

Listening to each woman as she tells her story, I can’t help but wonder: What makes these women so special? What is it that gives them strength to overcome the challenges of war, hatred, paralysis, political posturing, poverty, ignorance, and that mind-numbing inertia that always makes us think that someone else will do what needs to be done?

After enduring great pain, immaculée Ilibagiza is now showing others how to heal and forgive.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Immaculée

Ilibagiza:

A Lesson in Forgiveness

When rampaging Hutu tribesmen went on a killing spree in 1994 that left one million Tutsi dead across the African nation of Rwanda in the space of 100 days, 22-year-old Immaculée Ilibagiza was an engineering student at the National University, home with her family to celebrate the Easter holidays.

Without warning, simmering ethnic hatred erupted into flames. Her parents—respected Tutsi teachers in the village of Mataba—stayed to organize their neighbors and defend their home, but sent Immaculée to stay with a local Hutu pastor, the father of one of her friends.

As fighting broke out, Pastor Murinzi hid Immaculée and seven other women in a bathroom four feet long and three feet wide, with a small window high overhead. It was big enough for a tiled shower stall and a toilet. The women took turns standing and sitting, sometimes sleeping one on top of the other. They couldn't make a sound for fear the pastor's family would hear, so they worked out a form of sign language. Pastor Murinzi occasionally brought them a small plate of food, and they took turns stretching. As Immaculée writes in her book Left to Tell:

It was my turn to stretch when a commotion erupted outside. I stood on my tiptoes and peeked out the window through a little hole in the curtain.

Hundreds of people surrounded the house, many of whom were dressed like devils, wearing skirts of tree bark and shirts of dried banana leaves, and some even had goat horns strapped onto their heads.

They whooped and hollered. They jumped about, waving spears, machetes, and knives in the air. They chanted a chilling song of genocide while doing a dance of death: “Kill them, kill them, kill them all: kill them big and kill them small! Kill the old and kill the young...a baby snake is still a snake, kill it, too, let none escape! Kill them, kill them, kill them all!”

I recognized dozens of Mataba’s most prominent citizens in the mob, all of whom were in a killing frenzy, ranting and screaming for Tutsi blood. The killers leading the group pushed their way into the pastor's house, and suddenly the chanting was coming from all directions.

Immaculée, a deeply religious woman, began to pray. For 12 to 13 hours a day over the next three months, she prayed. Starting at dawn, she thanked God for saving the women in the bathroom, prayed the various prayers associated with her rosary, prayed for her friends and family. The only people she couldn't pray for were the killers outside. She knew her Christian faith required her to pray “for those who have sinned against us,” but she couldn't bring herself to do it. And that in itself became something to pray about.

Finally, one night a baby was left to die on the road outside Immaculée’s hiding place. It cried all night. By morning, it only whimpered. By nightfall, there was no sound but that of snarling dogs. Immaculée could take no more. “How can I forgive people who would do such a thing to an infant?" she cried out in the silence.

And she heard the answer clearly: “You are all my children...”

In that moment Immaculée realized the breadth of God's love and forgiveness. It wasn't just for good people. Humbled, she was finally able to ask for forgiveness—for the killers and herself.

Weeks later, a French rescue force and a Rwandan rebel army entered the country, and Immaculée and the other women fled the pastor's bathroom to reach them. She had dropped from 115 pounds to 65 by that time, but her rescuers saw that her spirit burned brighter than ever. She endured because of her strength, and “The source of my strength is God Almighty,” she says today.

For now, Immaculée lives on Long Island with her husband, a United Nations diplomat, and two young children. She heads the Left to Tell Foundation, which is working to heal the people of Rwanda “one heart at a time.” And although it would be easy to

lose herself in the sweetness of home and family, she has begun to travel all across the United States to tell groups what happened in Rwanda, how healing begins—and how is always the first step.

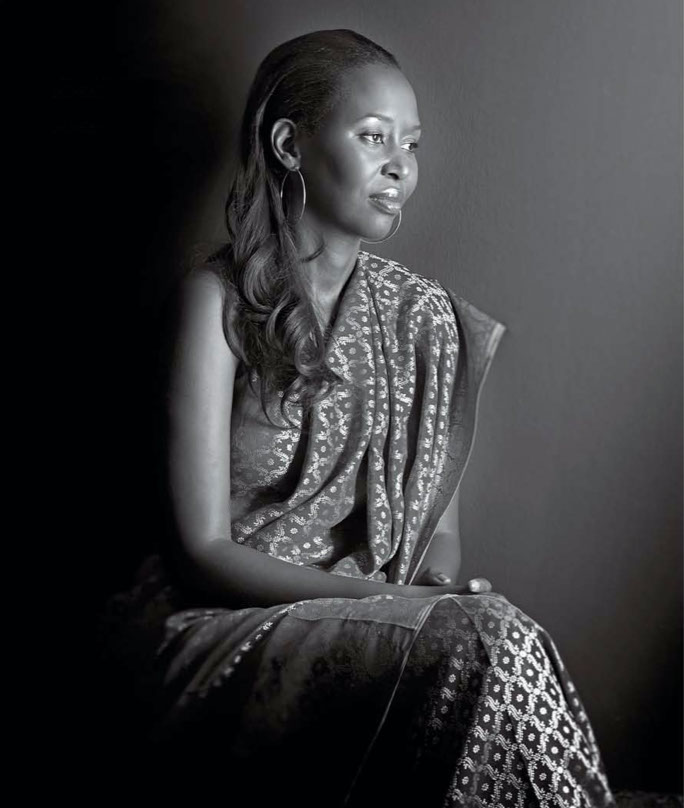

Evie Rosen's group has knitted afghans for hundreds of thousands of homeless people.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Evie Rosen:

Comforting the Homeless

For 80-year-old Evie Rosen, it wasn't so much her faith as a stubborn determination that something simply had to be done on behalf of homeless people in this country. When she heard that increasing numbers of confused and homeless men and women were spending their nights on the streets, she turned a handful of caring knitters in Wisconsin into a nationwide group of volunteers armed with knitting needles. To date, Evie's army has knitted more than 280,000 afghans to bring comfort and

warmth to those who have been left on America’s doorstep.

“It was in the "60s," Evie remembers. “People kept coming in to my yarn store and saying, “What should I do with this leftover yarn? There was a lot on the news about homeless people, so I suggested we knit 7-by-9-inch squares and sew them into afghans.”

Evie laughs. “It grew like crazy. People would send boxes of squares and drop off bags of squares—and people who couldn't knit or crochet would sew them together. People came to my shop to sew together, and one Saturday we met at the local mall and even more joined us."

Pretty soon it seemed as though half the town of Wausau, Wisconsin, was knitting, crocheting, or sewing afghans. And then word began to spread even farther. “Different groups across the country adopted the project,” says Evie. “There was even one insurance company in New York that bought yarn, and their employees worked on the afghans on their lunch hours!”

It was tough to manage so many eager volunteers scattered all over the country. But Evie prevailed, all the while juggling the yarn shop and knitting classes. So far, more than 280,000 afghans have been donated to homeless shelters, nursing homes,

children’s hospitals, veterans’ homes—even many of the survivors of Hurricane Katrina are wrapped in Evie’s warmth.

Today, even though she's given up the yarn shop and passed on the afghan project to Warm Up, America!, a project of the Craft Yarn Council of America, people send Evie knitted squares. She laughs, "I opened the door this morning and there were three bags of squares sitting on the back porch!” But, at 80, she's throwing in the towel—er, afghan. “Please,” she begs, “send the squares to Warm Up America! Foundation. They'll send them where they're needed.

"Just don't stop making them,” she adds. “An afghan is a gift of love.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Susan Corson-Finnerty:

Reclaiming a Lost Child

Love is something that Susan Corson-Finnerty understands well—and it has driven her since she was an 18-year-old undergraduate at Ohio State. Naive and inexperienced, she became pregnant “not by choice,” as she says, and was persuaded by her family to give up the child—a boy—for adoption.

“It was the wrong decision,” says Susan, an Abington, Pennsylvania, Curves member, today. “And against the grain of who I am.”

But caught in the maelstrom of middle-class parents shamed by her pregnancy, an adoption agency's social worker who was less than mother-friendly, and her own lack of wisdom and courage, it was a year before Susan could struggle through the grief and confusion to realize that she should have kept her son. Tragically, once she realized her mistake, it didn't take long to realize that it would be traumatic for both her son and his adoptive family if she were to reappear in his young life. So Susan sealed the pain and grief inside her heart, and vowed to wait until the boy grew up. Once he was an adult, Susan knew that she would need to find him.

Prompted by a National Public Radio discussion of the bonds between adopted children and their birth moms, 23 years later Susan felt that it was time to look. “I wanted him to know his birth family and to understand at an experiential, gut level how deeply related we are. I wanted him to experience the kinship bond, a precious gift that only the birth family can give. And I wanted all of my children"—by then, Susan was married and had two other children—"to be in relationship to each other and to me."

Once Susan had found her firstborn, who had been named Paul, it didn't take long. He began to spend time first with her, then with his siblings and stepfather. He eventually moved in with her family and spent four years as a member of the household.

Even more miraculous, however, is the fact that Susan, who was determined to spare Paul the agony of having two mothers competing for his love and attention, reached out to Paul's adoptive mother as well. It was a delicate undertaking, Susan admits. But as a result, “His adoptive mother and I formed a deep bond. We both wanted what was best for Paul.”

The two women became close, and when Paul's adoptive mother died of a heart attack four years alter they met, Susan grieved deeply. “Spiritually,” she says, “I felt we were co-mothers of our son. To lose her was a terrible blow for me as well as her family.

So what gave Susan the strength to integrate the two families? “Love for my son,” she says simply. “And faith that God would guide me.”

What keeps her going? “You meet children who have had the most horrendous things done to them, children who have been forced to do the most horrendous things themselves in order to survive, you see children deprived of the most basic things, but you also see this amazing testimony of the human spirit—resiliency,” says Christine. “People deal with these situations with grace and strength.

“They are"—she searches for words that can convey the depth of her respect—“an inspiration.”

As inspiring as the adults and children may be, however, the fact is that the needs of children are often overlooked when a country is in crisis. Government and relief officials quite rightly take care of feeding and sheltering small children first, says Christine, but older children and their protection are ignored. The tragedy is that in country after country, Christine has found that child protection continues to be considered a secondary priority.

"Families are a child's best protector,” says Christine. “Communities know how to protect their children as well. Even in places where people have been forced to flee their homes, there is still a high degree of community cohesion.”

Unfortunately, every time there's a crisis, countries and relief agencies forget this important lesson—which is why Save the Children has sent Christine to the United Nations in Geneva to work with the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

“My job is to make sure that children’s issues aren't overlooked in an international response,” she says. “There are 9 million displaced children in the world. I try to honor the voice that they've entrusted to me.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Christine

Knudson:

Saving the World's Children

When the tsunami swept across Banda Aceh two years ago, 39-year-old Christine Knudsen was right behind it. For Christine, it's the communities she serves—and the generations of strong women from which she comes—that give her the strength to move rapidly around the globe from one crisis to another.

As senior protection officer for Save the Children, it’s Christine's job to protect children who have survived war and natural disaster. When the tsunami hit, for example, Christine, working with the Acehnese communities, coordinated efforts to help round up more than 5,000 children who had become separated from their parents, worked to reunite the children with their families, and set up 59 safe play spaces” in temporary camps throughout the province, which benefited more than 6,500 children aged 3 through 12. Not only would the spaces offer children a place to begin coming to terms with their loss and fear after the tsunami, it also would give them a place to be safe while their families and communities began rebuilding.

She has done similar work in Afghanistan, Burundi, Chad, Mozambique, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere—and was most recently in Sudan, checking on the safety and emotional well-being of 140,000 kids displaced by the persistent genocide that is sweeping the country. She has been caught in crossfire, blessed, caught in political coups, hugged, detained by rebels, and remained an advocate for the world’s forgotten children throughout it all.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Joni Eareckson Tada:

Hope on Wheels

Joni Eareckson Tada's own disability allowed her to bring love and hope to others.

When California author Joni Eareckson Tada, who had been paralyzed in a diving accident at age 17, discovered that people in poor countries who couldn't walk were frequently forced to crawl along the streets and alleyways of their towns and cities just to find food, she put her own wheelchair in gear and persuaded Americans to fix, donate, and deliver used wheelchairs to 35,000 men, women, and children in more than 70 countries.

It wasn't an accomplishment she envisioned after the dive that broke her neck. Then she begged friends to kill her. Instead, they helped her reframe what had happened in terms of her religious beliefs—she became very, very angry. How, she wanted to know, could a loving God have let this happen?

Through almost two years of rehabilitation, Joni struggled with her physical recovery and her anger at God. She emerged to write Joni, which catalogs those struggles and reaffirms her beliefs. An inspirational best seller, it gave hope to millions of readers, gave her a voice in the disability community, and catapulted her onto the world stage, At last count, Joni has been translated into 45 languages.

Joni was only the first of 35 books, all of which bring hope and love into their readers’ lives. But they are only a part of what Joni has found the strength to do. Now 59, she does a daily five-minute radio show, broadcast to 1,000 stations with more than a million listeners a week. She holds roughly 18 Family Retreats (joniandfriends.org) every year for special needs people and their families. She heads Wheels for the World, which collects, fixes, and ships wheelchairs for poor people. And she heads the Joni and Friends International Disability Center that works with the United Nations on disability issues and trains church staff and volunteers to work with those affected by disability.

And this is a woman who, literally, can’t lift a finger?

Joni chuckles. “I'm not a saint,” she says. “I wake up every morning and say, "Where am I going to find the strength to make it till lunch time?’

“That's what drives me to God,” she admits. “My weakness."

In a sense, she adds thoughtfully, “My weakness is my strength.”

Marie Pimentel says her faith allowed her to find a way to help the women and children in Africa.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Marie

Pimentel:

Swapping Fire

for the Sun

When I ask 78-year-old Marie Pimentel how a Wisconsin farm girl ended up teaching solar cooking to hundreds (that has grown to thousands) of women throughout Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Ghana, Rwanda, Turkey, Armenia, and Mexico, her laugh tumbles through the phone line. “It's a calling from the Holy Spirit,” she chuckles. “Opportunities have opened to us that wouldn't have otherwise. The fact that we have the energy and health to do this at our age, well, our doctors are amazed!"

The “we” of whom Marie speaks are she and her 81-year-old husband, Wilfred, who in 1969 packed up the family and moved to Nigeria to teach veterinary medicine and surgery. While there, the Pimentels noticed three things: One, that there were few trees, no new trees were being planted, and, as a result, the Sahara Desert was advancing southward. Two, that the smoky cooking fires women used were responsible for so many respiratory and eye ailments that experts suggested they were the equivalent of smoking 10 to 20 packs of cigarettes a day, And three, that women, who were responsible for cooking every day, were scrounging for wood and carrying huge baskets of firewood for long distances on their shoulders.

The Pimentels were upset, Not only were the women becoming ill and depleting a vanishing natural resource, but they were inadvertently endangering their infants. They carried the children wrapped and secured to their backs, and, not infrequently one of those huge baskets of firewood would slip and decapitate a child.

After Wilfred’s work was finished, the Pimentels went home to California and focused on raising their five teenage children. Then, in 1988, Marie heard about an international organization on solar cooking being formed in Sacramento, It turns out that a couple of cardboard boxes, some black spray paint, a dab or two of glue, and a roll of aluminum foil can create a “solar oven” box that captures the sunlight and converts it to heat energy that is transferred to the covered pot of food placed inside for cooking.

Remembering the decapitated children in Nigeria, Marie jumped on the idea. “We wondered how it could be applied to Africa.”

Nigeria was unstable at the time, but by 1994 Marie and Wilfred were able to meet with people in Kenya to generate interest in applying for a grant from the Rotary International Foundation to look at a plan to help preserve the disappearing forests and woodlands, provide safe drinking water, and improve the quality of life and nutrition for the people, (Rotary International is a volunteer organization made up of business and professional leaders.) Marie and Wilfred met with the organization's clubs in Nairobi to ask members what they thought of the solar cooker, evaluate the Kenyans’ needs, and figure out how people might best be trained to use the cooker. With help from Rotary clubs, the Pimentels found nongovernmental church and community

groups that could bring people together for training, then follow up to see and resolve any concerns by the users of the cookers.

Recruitment wasn't easy. “You're taking women who have been building fires for most of their lives and telling them they can use sunshine instead,” says Marie. “That's asking for a leap of faith!"

Nevertheless, it's a leap the women of Kenya made—and, to date, the women of 11 other countries as well. Today, 12 years later and 35 years after she became aware of the effects of wood cooking fires on the Nigerian women and children, Marie is still

returning to Africa and other project sites several times a year.

“After all these years, it’s like going home,” says Marie, who refuses to let the aches and pains of aging slow her down. “The people are wonderful. They're so poor, but they're so generous.”

The trip is arduous, she admits. “We're up and running by 6 every morning, and by 8 or 8:30 at night we're ready to drop.” She laughs delightedly. “Our faith and the prayers of many have given us the strength we need,” she says firmly, “There are so many good people in the world. And there's so much to do.”

ELLEN MICHAUD is a contributing editor to diane.