How four people found happiness in lives filled with purpose and meaning.

by Ellen Michaud

Studies suggest that happiness slips into our souls on the heels of a life full of passion, rich with purpose and overflowing with meaning. But where does that passion, purpose and meaning come from? And how do they make us so happy?

“Purpose is central to a person’s life narrative,” says psychologist Patrick E. McKnight, Ph.D., of George Mason University. “It offers direction, just as a compass offers direction to a navigator.” On its own, purpose organizes and stimulates goals, manages behaviors and provides a sense of meaning.

Essentially, he adds, “it puts a to-do list right in front of you.” But it also awakens the passion that will keep you working hard. It gives you a reason to get up in the morning, eat your veggies and get a good night’s sleep. It keeps you focused—it ignites a commitment that keeps you moving ahead through every challenge. What results is a meaningful life, filled with happiness, a deep sense of satisfaction and connectedness as its residue.

How Do You Find Your Purpose?

Today, purpose, passion, meaning and happiness are hot topics of research at major universities across the country. Brain-imaging studies track which parts of the brain are involved.

Neuropsychological studies measure chemical messengers zipping around your body delivering and modifying the brain’s instructions. And cognitive studies identify the behaviors triggered.

“Our goal is to figure out precisely how purpose, passion and meaning work together,” Patrick says. “Half the time, we’re driving blind, but some studies are converging on similar views and outcomes.”

While researchers work out the links, however, the hardest part of finding a happy life for some of us may simply be discovering a purpose that will drive the train. Case in point: A study from the University of Colorado found that 40 percent of us don’t have a clue as to what our purpose in life might be.

So how do we get past that? How do we find something that will deliver the goods?

“Sometimes [discovering purpose is] just a chance occurrence that reveals to someone what their purpose should be,” Patrick says. “Sometimes it’s a tragedy, like the death of a child. Or sometimes it’s happenstance, it’s a close call that makes someone think, ‘I’ve been given a second chance, and I’m going to do something that makes a difference in people’s lives.’”

But sometimes, he adds, it’s just looking at someone else who has a strong purpose. “It’s what one of my colleagues calls the ‘nudge effect.’ You’re miserable at work, you walk by somebody who’s smiling, and you start to think, ‘Huh. I can be happy, too.’”

Could discovering our purpose in life really be that simple? Meet four people from across the United States who are living out their purposes and discovering lives of passion, meaning and happiness they never could

have predicted.

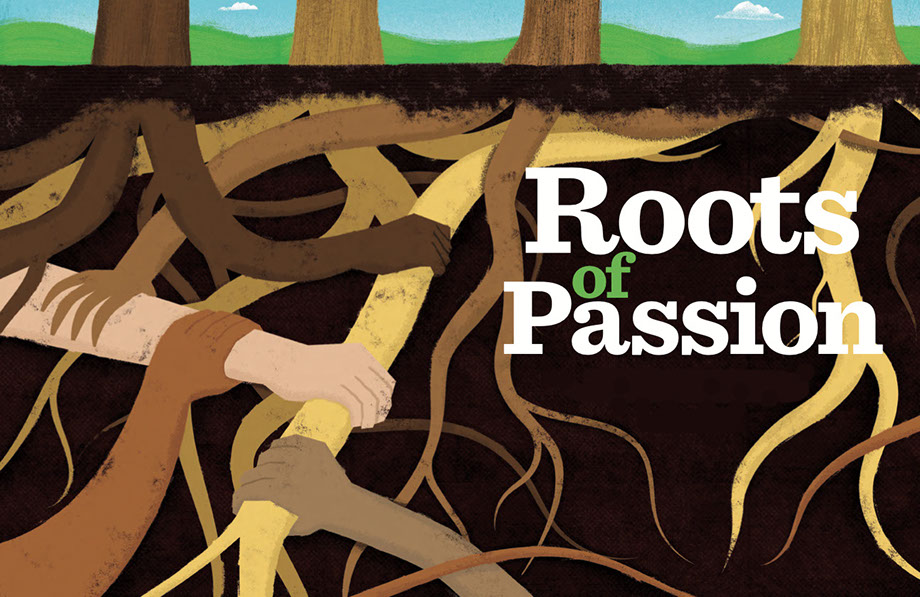

PHOTOGRAPH: ©NANCIE BATTAGLIA

Bill McKibbin: Saving the Earth

Many of us who grew up bribing our moms to drive us to the movies in the family gas guzzler and merrily spraying ourselves with insecticide at camp had no idea that, molecule by molecule, we were tossing damaged carbon particles into the atmosphere and contributing to a larger global problem. Fortunately, while so many of us were picking out a new shade of petroleum-based nail polish at the dime store counter, Bill McKibben, a tall, lanky kid from Boston, was hiking with his dad through the mountains and falling in love with the beauty of the planet’s forests, lakes, mountains and deserts.

That love, plus an avid curiosity and a sharp intellect that demanded to know how and who and why about everything, have thrust Bill into the forefront of a worldwide movement to reduce carbon particles thrown into the atmosphere by deforestation, aging agricultural practices, idling cars, home furnaces and fossil fuel-burning industries.

His awareness of the sheer physicality of the universe—and how we are impacting it on a daily basis—reached critical mass after he finished college and went to work for The New Yorker in Manhattan. “I wrote a long piece about where everything in my apartment came from,” Bill says. “I followed the electric lines back to the oil wells in Brazil and the uranium mines in the Grand Canyon, traced New York’s water system, on and on. It taught me that the world is a remarkably physical place, which is a lesson that’s easy to forget. That set me up nicely for reading the early science on climate change in the 1980s and recognizing the planet’s vulnerability.”

It also gave him a purpose, one that drove everything he did from the minute he got up in the morning until he went to bed at night, and lit a passion within him to share what was happening to the planet with every one of us.

Passion for the Planet

Bill’s passion to save the planet also led him to big questions—“How much human intervention can a place stand before it loses the essence of its nature?”—and to a purposeful exploration of one strategy after another: simple living, alternative energy, locally sourced food, birth control, new ways of living off the land.

Eventually, his belief that the planet could be saved by such seemingly simple practices led him to take action. So he and a group of friends took to the streets and founded the climate change organization 350.org. In the past few years, the organization, with Bill at its helm, has organized more than 15,000 rallies in nearly 200 countries, including the People’s Climate March in New York just before the U.N.’s September climate change summit.

The group’s tactics are working. They’ve helped raise the whole concept of sustainability to a national debate and have attracted enough attention that decision makers are hearing the roar. In one case, that roar helped convince the World Council of Churches, which represents 500 million Christians in 110 countries and territories around the globe, to dump its investments in fossil fuels.

While some don’t agree with all of Bill’s stances, his efforts have won accolades from others. He received the Right Livelihood Award, considered the “alternative Nobel,” in 2014 and has been named the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the 2013 winner of both the Gandhi Prize and the Thomas Merton Prize—and Foreign Policy, a journal, named him to its 2009 list of the 100 most important global thinkers.

Bill continues to move forward boldly and with purpose to achieve even more.

PHOTOGRAPH: ©OLIVER PARINI

Michael Wood-Lewis: A New Way to Connect a Community

Sitting at the edge of his white Victorian porch a few blocks from the shore of Lake Champlain, Vermont engineer and social entrepreneur Michael Wood- Lewis leans back in his chair, crosses one ankle over a khaki-covered knee, and looks down the shady street lined with oaks and older, well-loved homes.

“Hey—” He nods to a young neighbor walking down the sidewalk. “How’s it going?” The young man, a violin case strapped to his back, pauses, and the two chat for a few minutes about music, music teachers, performers and what’s going on in the neighborhood.

It’s a simple moment, an instant of connection, and the kind of conversation Michael loves and initiates a half-dozen times a day with neighbors, young and old. It’s also the kind of connection that characterized the Ohio community in which he grew up—the kind in which people dropped by the house with casseroles when Michael’s mom was ill with cancer and where he’d delivered newspapers on routes inherited from his older brothers.

“That kind of contact has always been important to me,” Michael says. It creates an awareness of the people around you, their needs, their strengths, what they have to offer. It’s what builds a group of people who will support one another, work together for common cause, or who will reach out to one another when help is needed. “It’s what builds a community.”

Unfortunately, when Michael and his wife, Valerie, moved to the Victorian 14 years ago, a sense of community is not what they found. People pretty much kept to themselves, Michael says. “You know the Robert Putnam book Bowling Alone? It was just like that.” Everyone was busy with their own lives, trying to make a living, keep their kids healthy, pay the mortgage and put one foot in front of the other.

Building a Network

So forging connections among his neighbors became Michael’s single-minded purpose. And, after several traditional approaches, he began thinking like the engineer he is: He started to build. In this case, it was a front porch on which people could gather. A digital one. If people had no time to sit around on their own front porches and chat with neighbors, he reasoned, then maybe they would at least cruise by a digital one while they were checking their emails.

The idea was that people from the five streets in his neighborhood and ZIP code would have access to the porch. They could post about anything—lost dogs, school candy sales, a visiting skunk, political candidates on the loose, new bus routes for kindergarteners, property tax hikes, whatever—connect, get to know each other and then take those relationships to the street. Then the next time they saw each other at the market, they’d stop and chat. Maybe introduce their spouses. Or kids. Or other neighbors. Civility and passionate discussion would be appreciated; bigotry and hate mail would not.

The idea was stunningly simple, and nearly everyone in Michael’s community joined the Front Porch Forum, as Michael finally called it. Today, eight years after its launch, the community-building service has helped spawn a number of other community- building services and is connecting 85,000 residents in Vermont, New York and New Hampshire. But, more important to Michael and the communities the website serves, anywhere from 50 to 75 percent of residents in each area where it’s available regularly hang out on their neighborhoods’ Front Porches.

“It’s gratifying to do work that’s clearly helping so many people in my broader community,” Michael says. “Especially as a parent of school-aged kids—it gives them an example of the kind of meaningful life I hope each of them will have.”

PHOTOGRAPH: ©PATRICK DOWNS

Jennifer States: Harnessing the Wind

Looking out from her office window in Port Angeles, Washington, toward the Strait of Juan de Fuca that separates Canada from the United States, Jennifer States talks quickly and with such excitement that one word tumbles over another and vibrates with energy.

“I was always passionate about the environment,” Jennifer says. “I grew up in a farming community in Nebraska with wind turbines on every farm. I majored in politics and government in school, but when I got out, I did some work for the Sierra Club, then started my own consulting firm.” Clients were few, but one, the Union of Concerned Scientists, gave her the gravitas she needed to be invited as a speaker to a Kansas conference on small wind.

“I did the presentation and somebody in the audience from an urban renewal company in Germany actually asked me if I’d be interested in heading up a wind group in Kansas,” Jennifer says.

She had no experience, but that wasn’t a deterrent. The company rep told her: “We’ve got the experience in Germany. We just need somebody who knows wind and politics in the Midwest.”

Jennifer laughs. “And I’m all of 26 years old, right?”

So she packed a bag, headed for Lawrence, Kansas, and became the managing director of JW Prairie Wind Power. “Getting wind to Kansas became a passion,” Jennifer says. She hit the ground running, working on legislation, dealing with state legislators and pulling together testimony for their committees. “I turned out to be a natural at talking with policymakers,” she says. “I’d hear them, hear their concerns, listen to others, hear their concerns, then figure out how one policy or another could be good for everyone.”

Unfortunately, Kansas rejected wind. So, Jennifer started thinking about another job. But just as she was about to begin making calls, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy research lab based in Richland, Washington, recruited her as its program manager. She accepted, moved to Washington with her husband, and took on the responsibility of developing

wind and water-power business.

“After a year on the job, I was asked to do an assignment in Washington, D.C.,” Jennifer says. The Obama administration had just come into office and they needed help. “I got a call from the Secretary of Energy’s office. We were in a recession and he wanted to know why renewable energy projects—wind, solar, hydro—weren’t being built.” Jennifer had 24 hours to find out, do some research, develop recommendations to rectify the situation and write them up.

“A month later, I could see the language I came up with in the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act.” She smiles. “The president signed it on my birthday.”

As a result of her work, over 20,000 renewable energy projects were funded—and Jennifer received the Women of Wind Energy Rising Star Award.

Several other assignments to governmental hot spots to solve energy problems kept Jennifer flying back and forth between the nation’s capital and her home with her husband in Washington state. Eventually, though, “I began to feel as though I were a bureaucrat pushing paper. I just wasn’t pursuing my passion anymore. And I missed my home.”

Today, back at home in Washington and with her cross-country flights behind her, Jennifer is the director of business development for the Port of Port Angeles and about to create an infrastructure that will stimulate growth of the area’s airport, marina, boat haven and deep-water terminals. It will also bring in a complex network of businesses, technology and skilled workers, providing the infrastructure necessary to support a floating offshore wind platform that will generate a significant amount of electric power for the nation’s West Coast. Looking out over a waterway that leads to the Pacific Ocean, Jennifer can see the sun setting in the west and envision a floating platform of wind turbines that will power the United States—and her passion—into the future.

Shane Claiborne: A Twist of Faith

Conversations with Shane Claiborne begin and end with laughter. Laughter when he talks about the pranks he and his buddies pulled rappelling down the side of a college dorm. Laughter when he recalls splashing through fire hydrant waterfalls with neighborhood kids on a steamy summer afternoon. Laughter when he talks about the night he and a bunch of homeless moms and kids in Philadelphia outsmarted a fire chief who was caving to political pressure.

Turns out, the chief was trying to evict the women and kids from an abandoned church in North Philadelphia’s “Badlands,” an area known for drugs, where they’d taken refuge from the cold autumn winds that swept off the Delaware River a few blocks away. The women had moved inside the church and were sleeping with their children on pews and on the floor in the unheated structure. Then the religious organization that owned the church wanted them out.

Shane and his buddies from Eastern University had been at the church to pray with the families and offer support. However, unbeknownst to the group, the city’s fire chief had scheduled a surprise inspection for 7 a.m. The plan was to inspect the church, “discover” a bunch of fire code violations, boot everyone out and then the police would enforce the order.

But not all of the rank-and-file firefighters were on board. Later that night, two firefighters arrived to tip off the families and help bring the church up to code. By dawn, with Shane, his friends, the firefighters and the mothers working all night, the church was in compliance with every requirement of the fire code. Fire extinguishers. Exit signs. Wiring. The whole enchilada. The chief arrived, stomped through the structure, then left. The moms and kids stayed, and Shane realized that he’d just stumbled into what he was supposed to do with his life.

The Simple Way

Shane is a radical. Make no mistake about it. He emerged out of the Bible Belt of East Tennessee, spent some time in his youth as a self-professed Jesus freak, attended a prestigious Christian college, grew a wild mane of dreadlocks, interned at arguably the largest, most-affluent Protestant church in America, and did graduate work at Princeton Theological Seminary.

But Shane doesn’t practice his faith in a traditional way. He does it by feeling his way along the path he senses God has laid out in front of him, one shaped by sleeping on the streets of Chicago with the homeless, working with Mother Teresa in Calcutta and breaking bread with the oppressed, the tortured and the abandoned. As he writes in his book, The Irresistible Revolution, “I learned more about God from the tears of homeless mothers than any systematic theology ever taught me.”

Pursuing this path has been Shane’s single-minded purpose for two decades. It’s not that he’s left the traditional practices of religious life behind. Prayer, caring for others, scripture, contemplation and communion are the touchstones of his existence. No, it’s more that he’s returning to simpler, more spiritual roots.

He’s ditched the big-mortgage church for a small community church in his neighborhood. He’s abandoned the pastoral manse for a fixer-upper row house in the Badlands that cost a few thousand dollars. And he’s helped create a small, intentional community of six to eight men and women who live and pray and work together every day of their lives.

That community, calling itself The Simple Way, is, as their website boldly declares, “a web of subversive friends conspiring to spread the vision of ‘Loving God, Loving People and Following Jesus’ in our neighborhoods and in our world.”

It’s a noble purpose. And fueled by their passion, the community members began getting the hang of how to do it. “When we started 16 years ago, we were reacting to crises,” Shane says. “We were feeding 100 people a day and trying to help people with housing issues.” There are still crises, he says, but over the years, the neighborhood has stabilized. Even when people have housing issues, they’re likely to stay in the neighborhood. And now the community has aquaponic systems, gardens, rain barrels and the ability to grow its own food. “One friend says we’re trying to bring the Garden of Eden to North Philadelphia,” he says.

But even the Garden of Eden had a touch of evil slithering around, and some days, Shane and his friends help their neighbors simply by accompanying them through the dark times. For example, a young man was shot dead on his block. (“Gun violence is a big focus here,” Shane says.) So the group supports its neighborhood by offering a loving presence and helping neighbors find ways to express their grief, their anger and their expectation of a better day.

At one gathering, the neighborhood came together to follow the biblical injunction to “turn swords into plowshares.” “We [had the guns melted], did a kind of welding workshop, got a forge and heated the guns,” he says. “Then the mothers who had lost kids to gun violence beat the guns into trowels.”

Using the trowels in the garden to grow food that would feed the next generation of kids was a powerful statement of the women’s determination that love would triumph over hate, forgiveness over anger, good over evil.

Acts like these have only shined the light brighter on Shane and his personal brand of the Christian lifestyle—and are attracting attention from across the religious spectrum. Each year, he receives invitations to speak at more than a hundred events in a dozen or more countries and nearly every state. He has led seminars at Vanderbilt University, Duke, Pepperdine, Wheaton College, Princeton and Harvard. And he has been publicly recognized by social leaders including Brian McLaren, one of Time’s 25 most influential evangelicals in America; Phyllis Tickle, former religion editor for Publishers Weekly; Archbishop Desmond Tutu; former President Jimmy Carter; and Tony Compolo, Ph.D., professor, pastor, author and former spiritual counselor to President Bill Clinton.

Shane may be on to something, with his simple, purposeful and passionate approach to faith, and maybe, just maybe, we could learn something from him.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ellen Michaud, editor at large for live happy magazine, is an award-winning writer who lives in Northern California. She has written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Better Homes and Gardens, Reader's Digest, Ladies' Home Journal and Prevention magazine.

Illustrations by John Coulter.

live happy magazine.