by Ellen Michaud

Home. The word resonates right to the center of who we are. It connects us to family, memories, our communities, even to ourselves.

center of who we are. It connects us to family, memories, our communities, even to ourselves.

For some, home is primarily a nest that nurtures, a refuge that protects, a delight that allows us to exercise the playful side of our natures. For others, it’s a sturdy structure of brick and mortar that anchors us—or a shell of aluminum that sets us free.

Even more, as architect Claire Cooper Marcus points out in her book, the aptly titled House as a Mirror of Self, our homes reflect our priorities, our values, and our histories—they are all on display through the places where we choose to live. On the following pages, you’ll meet some amazing people whose homes do just that. We think you’ll find their stories both familiar and surprising.

The manner in which we design, adapt, and furnish our homes says a great deal about who we are, too, as individuals, as families, and as a society. New homes are getting smaller—the era of the oversized “McMansion” is over (for now). At the same time, households are expanding to accommodate two, three, even four generations under one roof. Revolutionary products and services are allowing older homeowners to live long lives, safely, happily, and independently in the same house; meanwhile, wireless and integrated “smart” technologies let others redefine their notions of home entertainment, convenience, and comfort. As you’ll see, these and other housing trends in America are more than just the bloodless facts and statistics of a multibillion dollar industry—they are the very measure of our hopes and dreams.

As twilight settles over Boston’s historic Beacon Hill neighborhood, Victorian gaslights glow against the aged brick row houses that have stood here for close to 200 years.

Inside one of the elegant homes here, Susan McWhinney-Morse sits in the living room of her home and counts her blessings. “I have everything,” says the active septuagenarian. “A garden in back. A deck off the kitchen. A beautiful living room with high ceilings, exquisite plasterwork, and two wood-burning fireplaces. My four children all grew up in this house, and they loved it. They can’t imagine not coming home.”

The house has been through a lot of changes since Susan moved here with her first husband some 40 years ago. After that marriage ended in divorce, Susan took in boarders to support herself. Her family occupied three floors, but with other floors in the house, there was plenty of room for paying guests.

“The house has been so flexible,” Susan says. “When I married David Morse 15 years ago, the kids were all grown up, and we really didn’t need all this room. So we downsized within our own house. We turned the house into three separate apartments. We have the main floor, four bedrooms, and David and I each have our own study.”

To make sure that she and David are able to stay in their home as they age, Susan and her neighbors formed a community organization that offers services to Beacon Hill residents: dog walking, house painting, garden weeding, grocery shopping, rides to the airport, even someone to help rearrange the furniture.

“The idea was to be on Beacon Hill forever,” says Susan. “The people here have a great sense of community, of neighborhood, and of caring for who we are and what happens here. We started with 11 people who were wild about the idea, and it’s just grown.”

PHOTO BY ART ILLMAN

Ramona Creel and husband, Matt Boorstein, named their home on wheels Stella.

They share their RV home with two cats.

PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER OQUENDO

STELLA ROCKS. A 200-square-foot Airstream Excella, Stella measures 29 feet at her longest point. She’s covered in polished aluminum, and her interior boasts wood floors, custom cabinetry, an antique metal backsplash in the kitchen, a stained-glass window, sheer window treatments throughout, and a couch that flips into a bed. In short, all the comforts of home, for only $15,900, delivered to the Maryland driveway of Ramona Creel and her husband, Matt Boorstein.

“Stella’s hip and cool and awesome and I love her,” says Ramona. So much so, in fact, that she and Matt decided to sell their house, reinvent their careers, and take to the open road. Permanently.

“The house thing just wasn’t working for us,” says Ramona. and they were miserable in Maryland, spending nights and weekends fixing up the house and days working to pay for it. Plus, all that work cut into their travel time.

“Some people are perfectly content staying at home, living in the same town their whole lives, not really caring if they see the world,” Ramona writes from somewhere near Atlanta. or San Diego. Or maybe it was Louisiana. “Not me! I inherited busy feet from my father. Nothing excited him more than jumping in the car and taking off to someplace he had never been. I’m the same way.”

Matt is, too. Ramona’s husband was a military brat who grew up wandering the country. Initially he worked in interior design while Ramona, who has a degree in social work, found homes for displaced families in Florida.

Eventually, she started her own business as a professional organizer of homes and offices, while Matt started work developing her business’ Web site. To earn money and remain mobile, Matt morphed into a full-time Web designer. Now, Ramona coaches clients via the Web, with occasional meetings when Stella pulls into an RV park, and Mark runs his business online. Wherever they can hook up to a server, an electrical outlet, and a water faucet, they’re in business. It’s a life that suits them well. “It just feels like the right path,” says the woman with busy feet. “We didn’t want the house. We don’t need the big screen TV. We want the experiences.”

Where are they off to next?

Ramona laughs. “Florida. We follow the good weather.”

PHOTO BY PETER WADSWORTH

STANDING PROUDLY IN FRONT of the chicken coop on his grand-mother’s three-acre homestead in Starksboro, Vermont, 8-year-old Christopher Gravelle carefully holds out two eggs so fresh they’re still warm from the hen. He carefully explains to visitors the hows and whys of raising chickens as he walks toward their outdoor pen. His sister, Courtney, a 6-year-old blonde elf in a lavender parka and sparkly shoes, bounces along beside him. “Know what?” she asks, pointing across the yard. “That’s my bike!”

Along with their hens, bikes, and cats, Christopher and Courtney have lived here in the gray clapboard house all their lives. Their grandparents, Bob and Sue Baker, bought the property 28 years ago to raise their daughters—Lori, now 26, who works at a kitchen-and-bath shop in Burlington, 27-year-old Jessica, and 31-year-old Shelly, a stay-at-home mom to Christopher, Courtney, and 9-year-old Thomas.

“The house was old but the price was right,” says Sue. “and we liked the neighborhood.”

Situated between a two-lane rural highway and the wooded foothills of the Green Mountains, the house, with its fenced-in front yard, sits on one side of State Route 116 with neighboring homes spaced well apart. A cornfield is across the road.

“I love my property,” says Sue. “I have two apple trees, a big garden, a bird feeder, we’re bordered by Lewis Creek, and the kids can fish.”

The big draw for her was the yard. “When we first moved here, we had a maple tree by the fence that shaded the yard, and there was one that shaded the house,” Sue remembers. “Those girls could play in that yard all day. They had their swing out there, and it was nice. During the summer, you could sit in the living room and feel the breeze blowing through.”

As time went by, the kids grew up, Shelley got married and moved away, and Sue picked up part-time work at a local supermarket, a golf course, and a neighboring elementary school. But then Sue’s husband developed cancer, and nine years ago he died. Five months after that, Sue had a heart attack and quadruple bypass surgery.

Concerned, Shelley and her husband, Jason, moved back home with baby Thomas to give Sue a hand. Christopher and Courtney were born over the next couple of years, and things seemed to be getting back on track. Then Jason died of a heart attack, and Shelley was suddenly a single mother.

Things have been tough ever since. Sue was able to work part time as a cafeteria worker at the local Robinson Elementary School until her job was outsourced in budget cuts last spring. Lori has a job; Jessica and Shelley don’t. The family heated the house last winter with a woodstove and two kerosene heaters, but one of the heaters broke, and Sue didn’t have the money to fix it. That’s a concern in an area with below-zero temperatures in January.

But Sue shrugs it off. When something breaks down, generally the girls figure out how to fix it. “You learn this stuff as you go along,” says Sue. “We had a major toilet clog last week, so the girls became plumbers. They went and got plumbers’ snakes, took the toilet off, pushed the snakes through, had the septic tank pumped, and got it fixed.

“When you got family, you do what you’ve got to,” she adds. “This place has been a refuge for everybody.”

PHOTO BY PETER WADSWORTH

PHOTO BY ELLEN MICHAUD

Sue and granddaughter Courtney.

Everyone in Sue Baker’s house has a job. Grandson Christopher tends the chickens.

Benjamin Speed and his wife Sarina grew up on Maine’s rocky coast, exploring lighthouses and cracking lobster at the Bucks Harbor market. then they headed for college in Washington State, and, like so many children, vowed never to return home.

Benjamin Speed and his wife Sarina grew up on Maine’s rocky coast, exploring lighthouses and cracking lobster at the Bucks Harbor market. then they headed for college in Washington State, and, like so many children, vowed never to return home.

After they graduated, Sarina went to work as a jewelry designer; Ben worked as a videographer. Both realized just how deep their roots were embedded in Maine’s sandy soil, how much they missed their folks, and how strongly they felt that the children they would have should be raised close enough to know their grandparents.

The two returned to Maine and rented an apartment. Ben got a job teaching film production with a local school and picked up a few extra bucks videotaping weddings, while Sarina continued with her design work.

But paying all that money for rent really bugged the practical Sarina. So the couple, in their mid-20s at the time and with a baby on the way, decided to build a house. And not just any house, but one that reflected their values— something large enough to meet their needs, but small enough to respect the environment and leave a reasonable footprint on the planet. A footprint, in fact, that measured 18 feet by 18 feet.

“People don’t need as much space as they think,” says Sarina, who grew up in an even smaller house. “We can’t have huge groups of people over, but for three people it’s more than enough.”

Aside from leaving a smaller environmental footprint, the house also makes sense in the current economy. “I wanted to build something so that if our jobs didn’t work out, we could still afford our house,” Sarina says.

Borrowing as little as possible from the bank, and with help from friends and family, the Speeds built the two-bedroom house themselves. “We did the basic framing, roofing, shingling, and insulation,” Sarina says. “The stuff that would take us too long to learn we farmed out.” As a result, the house—including its foundation and the road leading to the house—cost just $55,000.

With son Noah now 41⁄2, and baby Larkin newly arrived, Sarina and Ben are planning to build on a third bedroom. “But the house will never be more than 800 square feet,” says Sarina, firmly. “And we’ll have the mortgage paid off by the time the kids go to college.”

PHOTO BY BRITTANY N. CARTER COURVILLE

PHOTO BY JEAN FISCHER

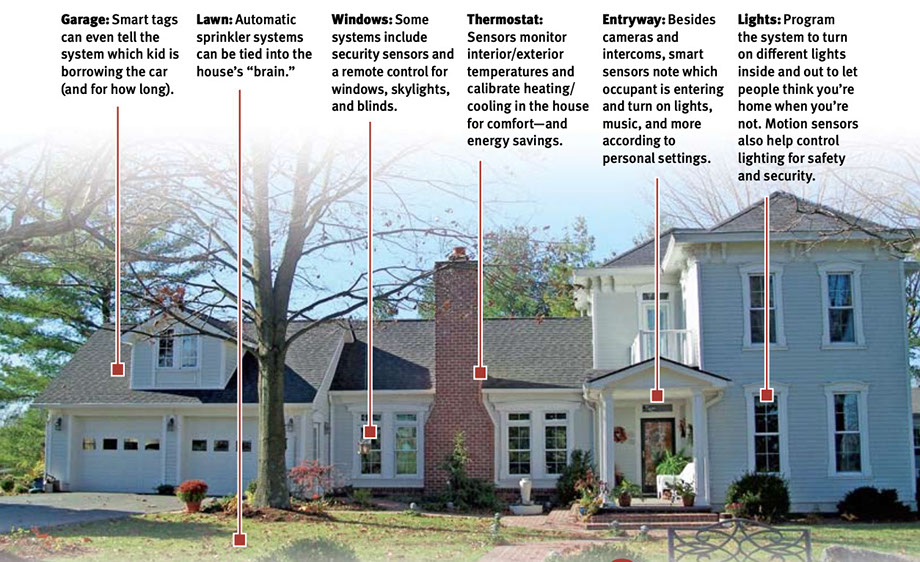

SMARTEST HOMES EVER As history has proven, new technologies—from electric lights and appliances to radios and televisions—inevitably make their way into the home. When they do, they make life easier, more efficient, and more fun.

Tony Tessaro would agree. Standing on Mandalay Beach in California, the 60-year-old retired Wall Street trader is like a kid with a new toy. Only that toy is his whole home. And it’s a smart home. “I can control everything from my TV clicker,” says Tony. “Say I’m watching TV and you ring the doorbell. There’s a camera in the bell, so a photo of you pops up on the screen.”

Tony loves that the house “knows” who he is. “We have a two-car garage,” he says. “One side’s me, one side’s my wife, Mary.” When the garage door opens and she drives in, the house senses it’s her, then closes the garage door, lights up a path to her bedroom, and turns on her favorite music.

Trends in home technology are changing the way we come home and what goes on in the home, from lights and music to control of heat pumps and central air for energy efficiency, says Laura Hubbard, a spokesperson for the Consumer Electronics Association.

Companies such as Russound, for instance, offer customizable equipment that plays music in different areas throughout your home from a single device, controlling the system with iPod-like keypads. Some systems read smart tags embedded in a phone or a keychain and respond according to the preferences of the tag’s owner.

While advanced systems can cost thousands and require extensive remodeling, the do-it-yourself route offers affordable off-the-shelf systems. Take HomePlug, for example: this concept allows TVs and computers to communicate via the home’s preexisting electrical wiring. Home automation is just the beginning, Hubbard says. In coming years, with the advent of the “smart grid”—a more efficient system of delivering electricity to your home—new home appliances will turn themselves on when it’s the most efficient time of day to do chores.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ellen Michaud is an award-winning writer who lives in Northern California. She has written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Better Homes and Gardens, Reader's Digest, Ladies' Home Journal, Prevention magazine and live happy magazine.

The Saturday Evening Post