By Ellen Michaud

Knitting Love Into the World, one Stitch at a Time

Two steps into the little yarn shop on Third Street, and I simply laughed in delight. To a woman with a passion for knitting, Knit Culture in Los Angeles is a whisper of heaven. From floor to ceiling, baskets, shelves and cubbies are stuffed with a thousand skeins of yarn from a thousand farms all over the world—neatly arranged by texture and color. Bamboo yarns from Sichuan Province in China. Silk yarns from a plantation in India. Plumped-up wooly rastas from sheep farms in Uruguay, cashmere from goat farms in Mongolia. Soft baby alpaca yarn from Vermont. And the colors! Passionate purples, demure beiges, moody sea greens, curried yellows, rich creams and wild oranges all reflect the warm California light from the store’s front window—judiciously aided by halogen spots that allow the colors to glow with energy.

Reverently, I reach out a hand to touch the delicate yarn of a baby alpaca, and I’m deftly caught in the eternal question of the passionate knitter: “What can I make with this?”

Cast On!

Somewhere around 28 million of us now regularly gather in yarn shops, knitting retreats and neighborhood knitting circles, so people are beginning to get used to us crazy knitters ooh-ing and ah-ing over a pile of yarn as though it were a baby. Today we knit everything from Christmas stockings to sweaters for family and friends. But according to the Craft Yarn Council of America, a whopping 49 percent of those who knit in the United States also spend time creating hats, socks, scarves, mittens and shawls for those who are ill, bereaved, abandoned, homeless and without hope.

The payback for our generosity is immediate. Knitters have found that soft yarn, rhythmic movements and yarn-besotted friends counter the hard stresses, isolation and frantic pace of daily life. And studies back us up. At Harvard Medical School, for example, one study suggests that knitting drops us into a relaxed, meditative state that reduces blood pressure, lowers heart rate and mobilizes the 40,000 genes in the body to induce changes that counteract the effects of stress. Another study, this one published in the British Journal of Occupational Therapy, found that 81 percent of study participants diagnosed with depression reported feeling happier after knitting—and half of them emphasized that they were “very” happy.

Knitting may cause the brain to release the feel-good neurotransmitter serotonin, explains Dr. Carrie Barron, a psychiatrist at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York and a knitter herself. What’s more, there’s some suggestion that engaging in any activity that releases serotonin on a regular basis can, over time, “train” the brain to release more of it, thus suggesting that a simple hobby like knitting can have a long-term effect on our happiness.

“We need more research,” Carrie says. “But I think we have a real need to make things. And knitting for others takes the effects of knitting on our psyche to a whole other level. It connects us to others in a very deep way.”

Save the Babies

Save the Babies

Few understand the deep connections knitting makes better than former Washington state social worker Jackie Lambert. Jackie is the caring woman who spends 40 hours a week knitting hats and sweaters for children who need them—particularly the Syrian children who now live in refugee camps in Jordan and throughout the Middle East.

Of the 3 million men, women and children who fled the brutality rampant in Syria over the past two years, nearly 740,000 ended up in Jordan only to find that winter in the desert manifests its own kind of brutality. “Millions of people left Syria with just the clothes on their back,” Jackie says. “Now they’re living in tents in the snow. Every child needs a hat, a sweater and a blanket, and nobody has socks.”

The U.N.’s World Health Organization stresses the need for hats to prevent life-threatening heat loss in babies, which is one reason why knitters around the world have had their needles clicking since the first wave of refugees left Syria. Two women from Ireland and an artist working with Save the Children in Syria launched a group called Save the Babies: Hats for War-Torn Syria, then put out an online call to knitters. The response was amazing. One newspaper reported 4,000 hats have been sent to Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp alone.

life-threatening heat loss in babies, which is one reason why knitters around the world have had their needles clicking since the first wave of refugees left Syria. Two women from Ireland and an artist working with Save the Children in Syria launched a group called Save the Babies: Hats for War-Torn Syria, then put out an online call to knitters. The response was amazing. One newspaper reported 4,000 hats have been sent to Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp alone.

“You hear horrific things on the news, but this is something you can do something about on a one-to-one basis,” Jackie says. “For every child who gets a hat and a sweater, that’s one kid who isn’t getting cold.”

Handmade Especially for You!

While some of us knit to keep people warm, others knit to bring them comfort. And that includes California transplant Leslye Borden. Leslye had always loved knitting, so when she retired from running her own photo-sourcing agency in New York, she figured she’d spend her time sitting in the sun with a pair of needles and a ball of yarn. “I made the most gorgeous things for my three granddaughters,” she chuckles.

“Beautiful sweaters, skirts, legwarmers, mittens, muffs—wherever they went people would stop them and ask, ‘Where did you get that?’ ” But as her daughter finally pointed out, how many sweaters, leg-warmers and mittens did the girls need? And where were they supposed to store them all? So Leslye looked around to find others who might need her gifts. She stumbled across an organization in Chicago that asked women to knit scarves for women who had been raped.

“Beautiful sweaters, skirts, legwarmers, mittens, muffs—wherever they went people would stop them and ask, ‘Where did you get that?’ ” But as her daughter finally pointed out, how many sweaters, leg-warmers and mittens did the girls need? And where were they supposed to store them all? So Leslye looked around to find others who might need her gifts. She stumbled across an organization in Chicago that asked women to knit scarves for women who had been raped.

“I had no idea when I made them what the scarves could do,” Leslye says. “I thought they’d be like a security blanket—something to hold on to.” But abused women told Leslye that the scarves felt like a hug around the neck and gave them a lift. And that’s all it took to yank her out of retirement.

“I was amazed by the response,” Leslye says. She founded Handmade Especially for You, a nonprofit organization based near her home in Rancho Palos Verdes, and decided to make whimsical, wildly colorful scarves for women in California who had escaped abusive situations. In 2008, she approached yarn shop owner June Grossberg, who’d opened Concepts in Yarn in Torrance, California, and got enough donated yarn to knit a trunk-full of scarves—plus space to hold a scarf-knitting group every Wednesday night that continues today.

Other yarn shops began sending Leslye yarn, knitters all over the state volunteered to help, and the next thing Leslye knew she was bagging yarn to send to knitters and shipping or delivering 12,000 scarves a year to 60 shelters throughout the state—each scarf with an attached tag signed by the knitter that says, “Made especially for you!”

“My husband and I used to have a beautiful home,” Leslye says, chuckling. “Now everything is yarn or scarves—bags of yarn waiting to be wrapped, boxes of yarn waiting to be shipped, and boxes of scarves waiting to be opened.” She laughs. “I just love it!”

A mother bear on the loose

Leslye is not the only knitter to find herself launching an organization in response to someone’s need for nurturing. When Amy Berman, a Minnesota sales representative and mother of two young children, read a magazine story on virgin rape in sub-Saharan Africa some years ago, it made her sick. The story revealed a cultural myth that having sex with a virgin—including toddlers and infants—would protect or cure men from AIDS.

to someone’s need for nurturing. When Amy Berman, a Minnesota sales representative and mother of two young children, read a magazine story on virgin rape in sub-Saharan Africa some years ago, it made her sick. The story revealed a cultural myth that having sex with a virgin—including toddlers and infants—would protect or cure men from AIDS.

The result was a practice that had left shattered children across the region and an increase in HIV and AIDS. “It was the most horrible thing I could think of,” says Amy, a former volunteer rape counselor. “Something that hurt kids and spread AIDS as well?” She shudders. “I had to do something.” Researching her options online, Amy found that South African police were asking for small gifts that might bring a tiny moment of comfort to the children touched by sexual violence.

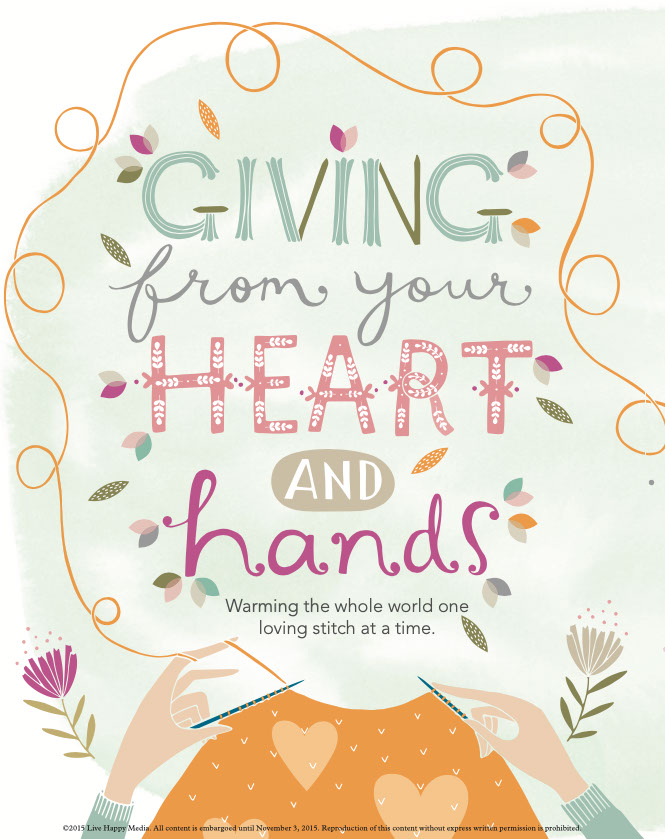

The image of her own kids cuddling the small, stuffed bears her mother had knitted for them flashed into her mind. The bears had comforted her kids when they were little. Could a group of knitters make them for children in Africa? Amy spoke to her mother, Gerre Hoffman, who was on board in an instant.

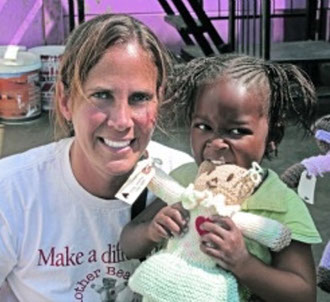

The two worked out four bear patterns, and gave them to anyone who could knit. Amy went to a yarn trade show to spread the word, her mother started giving knitting lessons, a newspaper did a story and, within weeks, 3,000 requests for patterns came pouring in—followed in short order by package after package of colorful hand-knit bears, each with personal touches added by its knitter.

The two worked out four bear patterns, and gave them to anyone who could knit. Amy went to a yarn trade show to spread the word, her mother started giving knitting lessons, a newspaper did a story and, within weeks, 3,000 requests for patterns came pouring in—followed in short order by package after package of colorful hand-knit bears, each with personal touches added by its knitter.

Amy chuckles. “The bears took over my house!” Friends, family and knitters flocked to help. Big red hearts were sewn onto each bear because Amy wanted kids who received the bears to feel that there was someone, somewhere, who loved them. Knitters also added a tag hand-signed by the “mother bear” who made the bear.

Amy made contacts in Africa, set up a distribution network, rented some storage space, and—borrowing the “mother bear” nickname with which her son had tagged her when he was a toddler—she named her emerging organization the Mother Bear Project. She also expanded the project to include those who had been orphaned by AIDS.

Today more than 110,000 bears made by more than a thousand knitters from all across the globe are carrying a mother bear’s love to children touched by HIV/AIDS.

Ripples of love

While small bears bring comfort to children in Africa, prayer shawls—made as the knitter prays for the recipient and weaves her blessings into the gift—bring comfort to adults who are hurting around the world. Few of the knitters realize that the idea to knit prayer shawls was hatched by two women who were attending Hartford Seminary in Connecticut nearly 20 years ago. Janet Severi Bristow and Victoria Cole-Galo saw the comfort a shawl touched by prayer brought to a grieving classmate whose husband had died. They launched “The Prayer Shawl Ministry” as both a spiritual practice for knitters and a source of comfort for those who received the gift of their work.

in Connecticut nearly 20 years ago. Janet Severi Bristow and Victoria Cole-Galo saw the comfort a shawl touched by prayer brought to a grieving classmate whose husband had died. They launched “The Prayer Shawl Ministry” as both a spiritual practice for knitters and a source of comfort for those who received the gift of their work.

Today, 3,000 prayer shawl groups around the world have made an uncountable number of shawls, and Janet and Vicky feel humbled by the work they were led to do. “It’s all been a surprise,” Janet says. “The emails, the [four] books we’ve written, the gatherings.…” She shakes her head in amazement. “It was truly out of our hands. It was nothing about us. It was what we were meant to do.”

Thinking about the 200 or so knitters who gather each November at a Hartford church to celebrate their work, she adds, “It touches me deeply that the love exhibited in that [church] ripples out to the world through the work of their hands and the prayers of their hearts.”

Listening to Janet, I look over at the tumble of colorful yarns tucked in a basket near my chair, and I realize that with a half-dozen balls of that yarn and a pair of bamboo needles, I can make my own ripples and give someone who is half a world away the sense of being wrapped in love. Slowly, I get up from my chair and move toward the basket—feeling my heart lift with joy.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ellen Michaud, editor at large for live happy magazine, is an award-winning writer who lives in Northern California. She has written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Better Homes and Gardens, Reader's Digest, Ladies' Home Journal and Prevention magazine.

Illustrations by Flora Waycott.

live happy magazine.